News Search

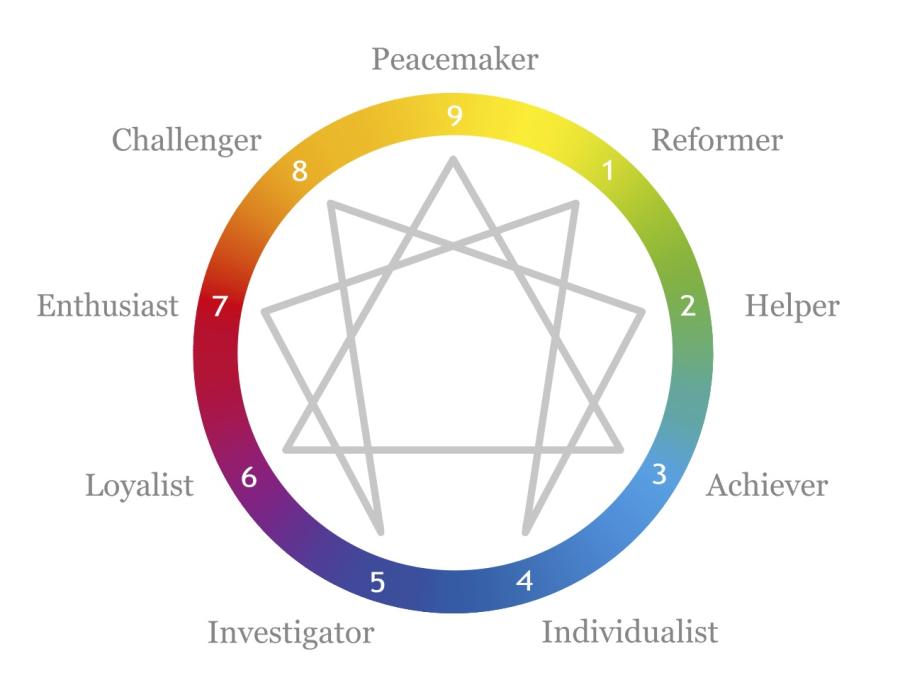

The Enneagram, unlike many modern-day personality tools such as the Myers-Briggs or the Birkman, can trace its roots to ancient times. The word itself is derived from the Greek words ennea (nine) and grammos (drawn symbol).

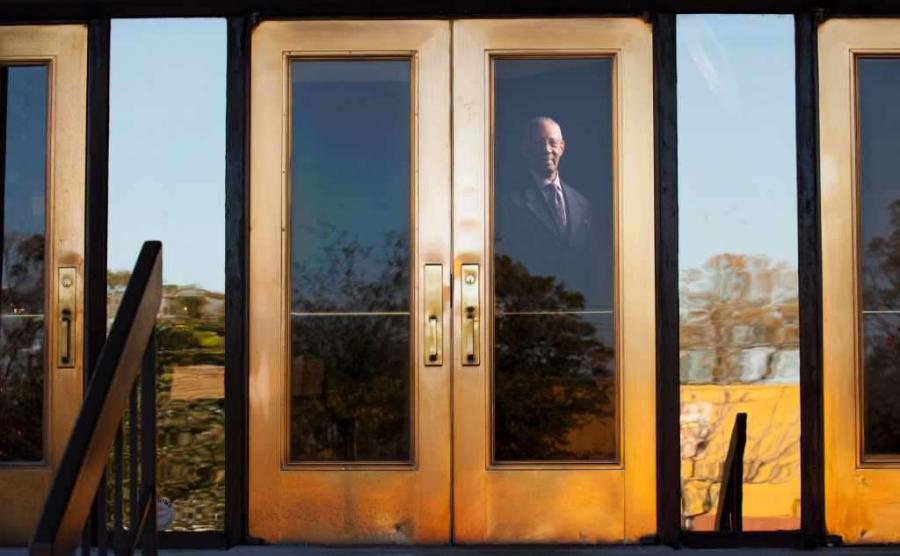

The Enneagram is represented by a circle with nine different starting points and nine equidistant lines drawn within the circle. It is meant to show nine different perspectives or “personalities” for how different people view and understand the world. The lines within the circle show how different personalities interact with each other in times of stress or growth. Numerous tests or checklists can be found online or in books to help someone identify which personality type resonates the most with themselves. However, as learned from Dr. Jon Singletary, Dean of the Garland School of Social Work, the Enneagram is so much more than just a test.

Dr. Singletary describes the Enneagram as a resource that can be used to better help us understand ourselves. He adds that the Enneagram can reveal more about how God has created us, is calling us, and transforming us.

Grief is a part of life for every person and, therefore, is a natural part of life for every church community.

Two of the most foundational duties of those in ministry are to walk alongside those who are grieving and to conduct funerals for the deceased and their loved ones. While the church is no stranger to grief, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented new challenges in how the church approaches and supports those grieving the loss of loved ones.

In honor of women’s history month, I want to take a moment to emphasize the diversity of women in Social Work, and acknowledge contributions to the work of intersectionality that encompasses women’s issues. “Social workers are tasked to examine roles, equity and fairness not only in the profession, but within society and with the women they serve each day (NASW, 2021).” The role of the social worker is to promote social justice in all aspects of life including advocating for meaningful change for a better tomorrow. Social work is an emerging field with women taking the lead in addressing women’s rights. According to CSWE Annual 2019 report, 74.1% full time faculty in accredited Social Work universities are women (Council on Social Work Education, 2019).

The Coronavirus, first declared as a global pandemic on March 11th, 2020, has impacted millions of individuals in a variety of ways. Across the nation, people have suffered financially, physically, and emotionally from the virus. As a result, an immense number of individuals’ mental health amongst every age group have taken an extreme toll. However, a prominent population that has been heavily impacted have been women.

According to research, the fatality rate for men has been twice as high than for women – however, the pandemic has impacted more women’s mental health than men. Because women represent the majority of the health workforce, they have been at a greater risk for COVID-19 and the emotional toll it comes with (Thibault, 2020). The effects of quarantine alone have caused many to feel isolated, lost, and scared, which is distressing for anyone – but add a susceptible population for increased mental health issues into the mix, and you have a recipe for disaster.

Because of the sensitivity and confidentiality of the people and location, this piece has been generalized to keep those involved safe and to challenge congregations of all sizes not to underestimate what they can do.

“We sometimes underestimate the influence of the little things.”—Charles W. Chesnutt

I am the kind of person that must be doing something “big” in order to think change will occur. However, I was challenged by the above quote from Chesnutt.

I was blessed recently to witness a church do something that in most eyes would seem small, insignificant and ordinary. Last week, I observed a small community church rally around one of their members, do the “little things” and, through them, advocate for this individual while also instilling a sense of hope.

Why it is so hard for some people of faith to own their own discomfort? To own their own fears and see how they injure others?

These are salient questions when it comes to creating caring Christian community for the LGBTQIA+ community. It is an even more relevant question for the leadership of my own university.

In the Bible, there are multiple references to people being known by their fruit and people’s actions being judged by their consequences.

Jesus’ fruit analogy seems to be one of the most useful lenses through which we can examine our words and actions. And it should help us provide clarity for any conversation about how we offer support to the LGBTQIA+ community.

People who are members of the LGBTQIA+ community do not harm or injure others in any way because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

The history of the Christian church includes many examples of addressing who belongs and who does not belong, starting at the very beginning.

Despite how clear Jesus was that women belonged, that Samaritans belonged and that lepers belonged, the early church struggled with whether or not Jesus came for the Gentiles as well as the Jews.

That seems obvious to us now (as most reading this are likely Gentiles, not Jews), but it was a matter of contention until both Peter and Paul understood God’s inclusion of all and spoke up and spoke out.

Phillip’s encounter with the Ethiopian Eunuch gave a concrete answer to the question, “Is there anything preventing me from being baptized?”

The answer, to someone barred from entering the sanctuary because of sexual difference, resounds through the years but often not through the church.

As a member of Protestant, often Baptist, congregations through the years, I have participated in the use of the words “Brother” and “Sister” to refer to other Christians.

If we are truly family, what does it mean when we cut off our siblings? When we make them hide or leave the family because they are different and unwelcome?

It didn’t take long for me to learn that what made me different was not always seen as beautiful by the world that existed outside the four walls that I was raised in.

My story is from a third generation Chinese American lens, who was raised in the Midwest and attended school in the south — please know this writing doesn’t encompass or represent all Asian American stories.

The white church in America is learning racism is not merely about our individual actions and decisions.

As a civil human being—more so as a child of God—we know better than to be racist, than to do racist things. In fact, in our effort not to be racists, we work hard to talk as though race doesn’t exist. Being colorblind was the way to be nonracist, we were taught. I suppose it meant if we didn’t see race, we couldn’t perpetuate it or contribute to racism.

The work of identifying racist attitudes and behaviors is not only uncomfortable but also never-ending, said Kerri Fisher, a lecturer and diversity educator at Baylor University.

Recognizing white privilege and oppressive social systems isn’t enough to sustain “cultural humility,” said Fisher, co-chair of the Race Equity Work Team in Baylor’s Diana R. Garland School of Social Work.

“There are always new ways to be unjust, so we have to always be learning,” she said.

“Cultural humility” describes an ability to critically self-reflect on the existence of cultural differences and impacts on marginalized groups with the goal being to build relationships with those groups, she explained.

Fisher outlined the process for achieving cultural humility, anti-racist and anti-oppressive attitudes during a recent interview with Baptist News Global.

Ruth was elderly, a widow, very hungry and giving $1,000 checks to anyone who came to her door if they would just bring her something to eat. Most took the money, but didn’t bring back any food. She gave her car away to someone who promised to bring her food. She was about to sign her house away when Adult Protective Services got involved. The court appointed a guardian for her who ensured she was never hungry again.

Stories like this can be heard time and time again, all across our country. The protection of vulnerable Americans has never been more important. In particular, persons with disabilities and advanced age live into devastating vulnerability, desperately in need of a trustworthy, well-informed and committed guardian. Baylor University’s Diana R. Garland School of Social Work (GSSW) and Friends for Life have partnered to offer an online educational opportunity for anyone wanting learn more about guardianship.

Mark Wingfield makes a compelling case that “You cannot follow Jesus and endorse racism.” However, he may have placed the “Period” of his title a little too soon.

I do believe the biggest problem in perpetuating racism is the “virulent white supremacist views” of people of faith, but I believe that virus is far more widespread than most of us white progressive Christians care to admit.

Let me be clear in my agreement with Wingfield. As he says, “The Jesus of the Gospels allows no room for being a racist or enabling racism. White supremacy and racism are wholly incompatible with a Jesus way of life.” And, Donald Trump’s white supremacy does contribute significantly to empowering hate groups and sustaining our culture of racism.

I was the pompous Christian college student who spent time with friends memorizing Scripture, even if I didn’t truly live them.

It was misplaced rigor, misguided piety and an out-of-focus faith. I could spit these passages out and talk about the virtue of humility, but practicing humility was not my strength.

My whole Christian fraternity and I memorized Philippians 2:3-8, but I missed the point. I had plenty of selfish ambition and was truly blind to what this passage meant.

Furthermore, my selfish ambition and vain conceit was tied up in my views of race.

Born in Vidor, Texas, a well-known sundown town, I was influenced by white supremacy in the earliest years of my life.

My white racial identity was a standard by which I compared myself to others and the norm against which others were seen as different or less than.

By white, I don’t simply mean skin color. White is not ethnicity or nationality. To be white is one thing, but the pride in whiteness is problematic given how whiteness was created to marginalize, oppress and enslave as part of our nation’s history.

WACO, Texas (July 20, 2020) – As individuals and institutions across the country consider necessary changes to effectively fight racism, two terms are gaining familiarity: cultural humility and antiracism.

Kerri Fisher, LCSW, an expert in cultural humility training and lecturer in Baylor University’s Diana R. Garland School of Social Work, defines those terms and shares five tips to help people cultivate cultural humility and antiracism in their personal and corporate lives.

“We are all impacted by the supremacist cultures that socialize us,” Fisher said, “so while we are not responsible for our first thought, we are responsible for our second thought and our first action. This means we must be brave enough to admit when our brain, body and behaviors are exhibiting racist reactions.”

Recently, I had the privilege of hearing from our Black social work students in a Listening Session hosted by our departmental administration. The students were vulnerable and raw and brave. They expressed exhaustion and hope and disappointment. They pointed out ways in which the Garland School of Social Work could be better, Baylor could be better, and our curriculum could be more inclusive and supportive. Many of our Black, Indigenous, and Students of Color have likely felt this for many years, but they finally had the collective voice and platform to express this hurt. I am thankful for them and to them.

As states re-open and congregations create their plans in response to COVID-19 for returning to corporate gatherings, the questions at hand may look very similar for church leaders: “How do we move forward? What do we need to consider or listen to? Who needs our care? How will our worship, fellowship and service look different going forward? What resources already exist in our community?”

According to study after study, college students suffer food insecurity at alarming rates. Many face the reality of having no idea where their next meal will come from. Houston MSW student Joyelle Gaines hopes, however, to make this a thing of the past with a new venture called the Joy Store.

The Joy Store is a student food pantry that opened this semester on our Houston Campus thanks to Joyelle’s advocacy, and she hopes it will help students just like her.

The past two weeks have been a whirlwind to say the least, shaking us to the very core, evoking mixed emotions from deep within namely: sorrow, grief, anger, frustration, fear, worry, depression, anxiety, confusion, tranquility, calmness, empathy, love, and gratitude. Everyday activities have come to a standstill as we are forced to stay at home; in a flash, life has turned upside down with death and destruction of people’s livelihood across a large number of nations. Suddenly, we are faced with a stressor called uncertainty, the fear of the unknown not just to us as individuals, but to us as citizens of this world. This monumental problem of COVID-19 has forced us into a crisis-mode, with great devastation caused by something only visible under the microscope; coming to us like a thief in the night confronting our very existence.

Grief can present itself in a number of different ways. It can manifest as anxiety or depression, or even depression and anxiety at the same time. We may notice changes in our own behavior we can’t explain, or maybe changes we don’t notice, but others do. That’s all the more reason to be patient with our loved ones, friends, strangers, and perhaps most importantly, ourselves.

The first step to approach and manage the condition of grief is to recognize and claim our feelings about what we’re experiencing. A lot of people aren’t accustomed to this, or it may make them uncomfortable, but almost the whole world is experiencing a collective grief right now, and if we can name and claim these feelings we’re having and talk about them with each other, we can begin to cope.

Maundy Thursday didn’t come naturally to me. Growing up Southern Baptist, we didn’t celebrate Holy Week, or much of anything from the church calendar, except for Christmas and Easter. In seminary, I remember being asked how you get to Easter if you don’t recognize Good Friday or Maundy Thursday.

These are disorienting times. Due to COVID-19, our professional, relational and recreational routines as American Christians have been disrupted by quarantines and social distancing. In our typically fast-paced world, it feels strange when things suddenly come to a halt. But what if God is using our disorientation for reorientation? What if, amid the coronavirus pandemic that now envelops us, we can rediscover the importance of Sabbath?

WACO, Texas (March 26, 2020) – For the week ending March 21, a record 3.28 million workers applied for unemployment benefits, a result of the sweeping economic consequences of COVID-19, according to a report from the U.S. Department of Labor.

In the proverbial “blink of an eye,” many find their neighbors, friends, family – and even themselves – out of jobs that only a few weeks ago seemed safe and secure.

The jobless are grieving. What’s our role? How do we help? How do we engage?

On Sunday I watched the news – until I couldn’t watch it any longer. I doubt I learned anything new during those three hours. I confess that I’ve never been much of a Sabbath observer, but I can say with confidence that there was nothing about Sunday that felt like a day of rest (except sleeping in and tuning into our church’s online worship service while still in my pajamas).

On Sunday I needed rest. I sat around all day, but it wasn’t rest. A big chunk of the day was spent consuming news that wasn’t new, except for the God-awful, rising number of COVID-19 cases and casualties, which only further prevented any sense of rest. Watching the news only fed fear and anxiety, doubt and disbelief.

#intimeslikethese

WACO, Texas (March 25, 2020) – In a difficult and ever-changing time of crisis surrounding the spread of coronavirus, the basic needs of health and safety come first. But as these basic physiological needs are met, the more advanced care for spiritual and mental health can remain overlooked or ignored altogether.

Baylor University’s Holly Oxhandler, Ph.D., LMSW., associate dean for research and faculty development and assistant professor the Diana R. Garland School of Social Work, is an expert on mental health, primarily anxiety and depression, as well as religion and spirituality in clinical practice.

WACO, Texas (March 17, 2020) – The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has announced that older adults and people who have serious chronic medical conditions such as heart disease, diabetes and lung disease are at a high risk for the coronavirus.

The virus hit hard in late January at a nursing facility in the state of Washington, where a number of residents died. As a result, the CDC has recommended strong restrictions on visitors to long-term care facilities, and the health organization continues to preach limited physical contact and “social distancing” – creating intentional space of six feet or more between each person – to stem the spread of the virus.

I’ve always considered myself an “outgoing introvert,” meaning I like people but prefer to be alone. It’s almost a week into social distancing, and I’m already starting to question if I’m actually a full-blown extrovert.

I find myself craving human interaction, and my house is feeling a little smaller than normal. My ongoing inner refrain has become, “This is what caring for your neighbor looks like,” and I’ve worked it into mindfulness exercises during these last few days.

What a difference a few weeks make in the way the world operates. Widespread limits on social interaction, closing of restaurants and other gathering places, and the moving of worship services to online-only experiences are just a few of the ways the world is a different place today. Political leaders insist the changes are both necessary and temporary. The importance of “flattening the curve” to reduce the rate of Coronavirus infection escalation is essential to protecting the most vulnerable among us. Limiting the size of crowds, elbow bumps instead of hugs, and three to six feet of space between us are some of the operationalizations of social distancing. Others include canceling sporting events and meeting for worship and education on-line.

The Family Health Center of Waco won an award from the Texas Academy of Family Physicians for its model of integrating behavioral health care into doctor visits in its 16 McLennan County clinics.

The Behavioral Health Integration Innovators Competition awarded three Texas clinics for their models of behavioral health integration into existing primary care settings, with a $10,000 prize.

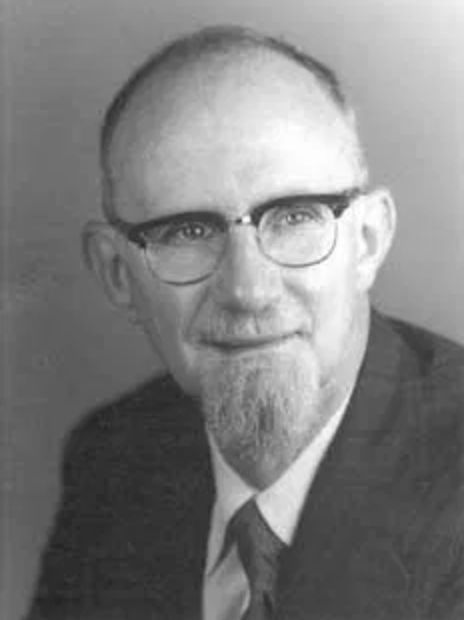

Dr. Alan Keith-Lucas (Keith) is one of the earliest and most influential leaders of the North American Association of Christians in Social Work (NACSW) and a seminal thinker and writer on the integration of Christian faith and social work practice. Many who knew him were both inspired by his understanding of faith and human behavior and energized by his practice wisdom as he valued every human being.

December 2019, Baylor's Diana R. Garland School of Social Work alongside Baylor's Office of External Affairs honored the BEAR Project as a Solid Gold Neighbor. The BEAR (Be Emotionally Aware and Responsive) Project, a collaboration between Baylor and Waco ISD, seeks to engage schools and families in the development of internal and external emotional resources that contribute to the social and academic success of children and, ultimately, strengthen Waco’s schools, families and community.

Formerly known as the Center for Family and Community Ministries, the Center for Church and Community Impact (C3I) seeks to strengthen congregations and other religious organizations by providing hands-on training and relevant research. C3I, like the Garland School of Social Work (GSSW) as a whole, believes in the importance of integrating social work and faith in order to foster collaboration and holistic care for others.

“Therefore, as you received Christ Jesus the Lord, so walk in him.” (Col. 2:6) While everyone’s walk with the Lord is different, Dr. Louis Gomez, MSW ’08, has found his calling by serving vulnerable populations.

This year, Gomez was named the chair of the Board of Advocates (BOA) at the Garland School of Social Work (GSSW) after being a loyal member for several years. Before joining the BOA, he was a part of the Houston Master of Social Work Committee, helping the GSSW open its second campus.

Last Sunday we drove nearly 500 miles from Waco to Brownsville, Texas, to pray. When we got there, what we really wanted to do was sneak through the fence, over a wall and through a window of the repurposed, former Walmart used to house children forcibly separated from their migrant parents.

We wanted to sit on the floor and hold babies, toddlers and preschoolers in our laps and wait with them until their mamas could come. We wanted to hear the names and listen to the stories of every child inside that facility. We wanted to shake the guards at the entrance by the shoulders and remind them that these are babies – children – someone else’s very best, most precious gift. We wanted to ask how on earth they could just stand there.

A few years ago, in memory of Founding Dean Diana Garland and as a way to honor her work, the Garland School created the Diana R. Garland Legacy Award. This year, we honor the School’s dear friend, Houstonian Rev. William “Bill” Lawson. In 1957, the Rev. William “Bill” Lawson, joined the Baylor Religious Hour as a guest preacher. The BSU leadership went about planning for the worship service as they had most Wednesdays that fall...

Austin artist Amie Stone King is proud to present her first art installation, Artifacts of Human Trafficking, at the Garland School of Social Work.

King first studied theatre as an undergraduate, then received a Masters of Art Museum Education. She has worked for years at various art museums, but found she wanted to do an exhibit on her own outside of a museum setting.

DALLAS—Baylor University faculty and staff joined colleagues at Baylor Scott and White in Dallas on Saturday to host the Third Annual Gil Taylor Behavioral Health Symposium. The event focused on “The Impact of Behavioral Health Issues Across Generations.”

Baylor Interim Provost Dr. Michael McLendon described how the event served to “strengthen our collective response in addressing behavioral health needs around the state.”

There are just some things we don’t talk about…

Baylor University’s Diana R. Garland School of Social Work presents: Artifacts of Human Trafficking.

And you’re so numb by that point, no, not even numb-that’s not the right word, you’re gone, you’re soulless. They own you, but not just your body, they own who you are, the deepest parts of you. –Anonymous

We invite you to shine a light into the darkness through art as we explore the pervasive sex trafficking industry in the United States through Artifacts of Human Trafficking, an installation created by Austin artist, Amie Stone King, with accompanying juried, 2-D mixed media works from artists around the world based on the themes of desperation, isolation and deceit.

When you hear the word “giving” associated with a university, your mind might jump to financial donations, but Angela Bailey believes giving up her time is even more important. Angela has been at Baylor University for more than 30 years, and she now serves as the program manager for both the PhD and Global Mission Leadership programs at the Garland School of Social Work where she works directly with the programs’ directors and students. She has grown up serving wherever she is needed, especially in her church.

Kendall Ellis has embarked on a quest to discern her vocation. It began with studying for a career in medicine when she, and her undergraduate work at Georgetown College in Kentucky, changed direction. “I ended up with a French degree and a minor in biology,” says Ellis, 24. Language study sparked a passion for cross-cultural experiences and how societies view and process life. That led to a tantalizing glimpse into social work.

A neighborhood school. Each morning children are dropped off at the front entrance of Brook Avenue Elementary School and personally greeted by Brook Avenue staff as they make their way to their classrooms. Each afternoon, those same families are congregated outside of the school waiting to walk home with their children. This is what a neighborhood school looks like.

WACO—Try to talk with Gaynor Yancey about needs and deficits, and before long, she will steer the conversation toward a discussion of assets and opportunities. Ask her to conduct a community assessment, and where others see overgrown vacant lots, she sees available space churches can use to plant community gardens or develop neighborhood parks.

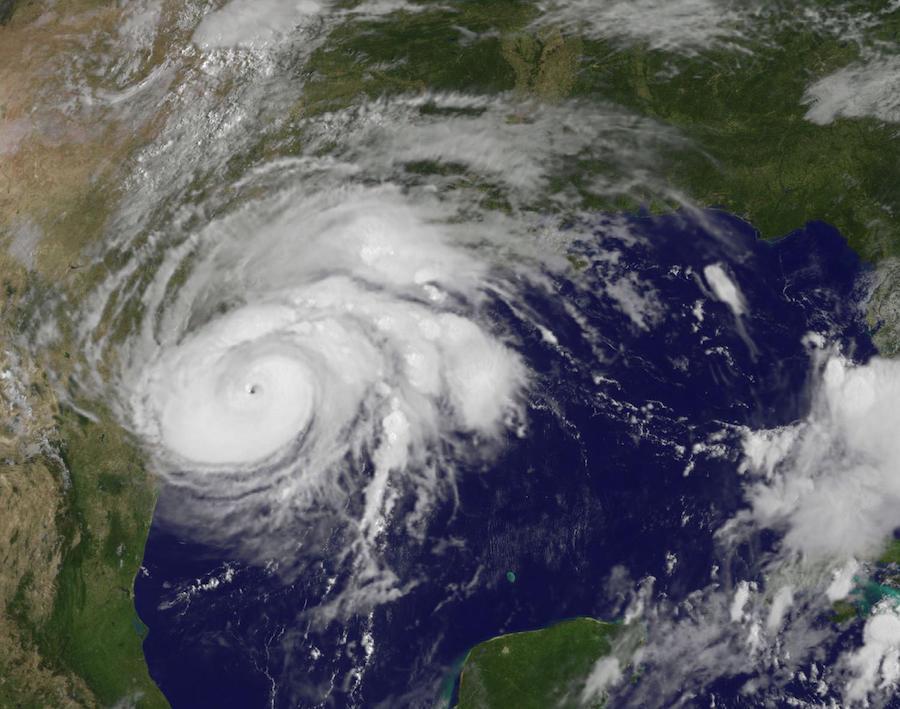

With Hurricane Harvey a few weeks in the past, and Hurricane Irma barreling through soon after, there is great need for volunteers to come in and render aid to those who were affected by these devastating natural disasters. Certainly, there will be much to clean up environmentally in the coming weeks, months, and even years, but there is also a great need for aid when it comes to helping those affected by the storm deal with the trauma they have faced.

The Hogg Foundation for Mental Health has awarded the Garland School of Social Work a $235,000 grant to expand programming aimed at addressing the mental health and wellness needs of students in the Waco Independent School District. The grant will be used to address the needs of students placed in disciplinary alternative education programs.